Looking for Butterflies

The fourth project at Metis invovles natural language processing (NLP) and unsupervisted learning.

NLP just means working with data written in English or another human language, rather than data in a computer-ready format such as a database or spreadsheet. Unsupervised learning means that a model attempts to organize the data automatically.

For my data, I decided to study the federal budget. Specifically, H.J. Res 31, the bill which ended the recent government shutdown and funded the government through September, 2019.

There’s probably a market out there for software that automatically keeps track of words going in and out of a complex bill as it works its way through the legislative process. Customers might include

- Congressional staffers

- Political activists

- Lobbyists

- Journalists

- Concerned citizens

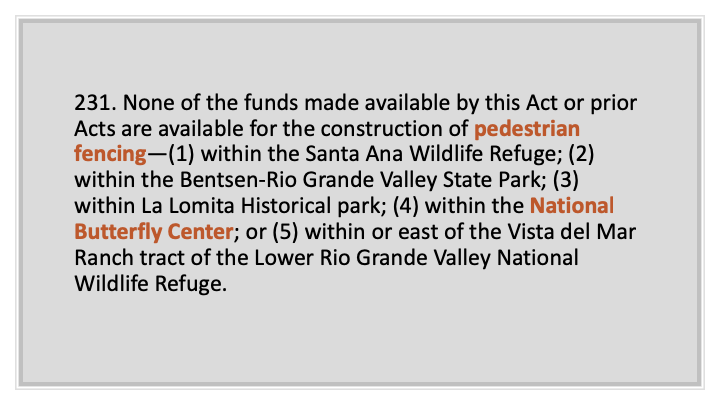

But, this was more of a curiosity-driven project for me. The idea came from an article I saw which mentioned that the most recent budget bill has a proviso that attempts to spare the National Butterfly Reserve from being destroyed by a border wall.

From the perspective of someone studying natural language processing, I wondered

- How often does a word like ‘butterfly’ appear in the Federal budget?

- Could I use natural language processing to identify provisions buried in a large piece of legislation to address a particular local issue or special interest?

So, I downloaded the XML version federal budget, parsed the entries into separate documents with BeautifulSoup, and created natural language processing models using gensim, a python library for analyzing document similarity.

Exploratory Data Analysis

So, what’s in an entry in the federal budget?

- Numbers. With dollar signs.

- Stop words: Stop words are small words like ‘and’ or ‘the’ that are typically discarded when analyzing a document because they are so common they do not help a computer distinguish one document from another.

- Budget/legal stopwords. I added my own budget stop words like ‘cost’, ‘expense’, ‘expenditure’, and legal stop words like ‘title’, ‘subsection’, ‘law’. (The budget cites numerous laws that require Congress to allocate money for something or that specify how an allocation is to be spent.) These words that indicate that I’m in a financial and government document, but they weren’t terms that I wanted to use to group documents because their presence doesn’t meaningfully distinguish one budget entry from another.

- Unique words. There are a surprising number of unique words in the budget. Most of the remaining words not in the above categories are either unqiue to the particular section of the budget or are only repeated in a small number of other sections. The majority of the vocabulary (after removing stopwords) is used in 5 percent or fewer of the documents.

There is no single explanation for the unique words. Sometimes it’s because there’s an unusual proviso, like my proviso for butterfly habitat. Sometimes it’s just a side effect of the fact that the budget includes a list of all the departments of the government. For example, the allocation for the Supreme Court is the only budget section with the word ‘supreme.’ Some of the unique words are common English words like ‘beginning.’ These are words that you might expect to see more than once in a 200,000+ word sample of English, assuming you had a normal sample of English rather than the federal budget.

So yes, there is only one ‘butterfly’ in the budget, but the same is true for more words than you might think.

Cluster analysis

Those unique words are a real problem for doing document similarity. The underlying assumption is that you locate similar documents by identifying words that documents have in common. You can’t easily make clusters if the words are scattered randomly throughout the corpus. (Corpus is just machine-learning speak for ‘group of documents.’)

Traditional cluster analysis did allow me to find sections of the budget that are exact duplicates or nearly so. For example, this text (with a different section number) appears in seven locations:

SEC. 523. (a) None of the funds made available in this Act may be used to maintain or establish a computer network unless such network blocks the viewing, downloading, and exchanging of pornography. (b) Nothing in subsection (a) shall limit the use of funds necessary for any Federal, State, tribal, or local law enforcement agency or any other entity carrying out criminal investigations, prosecution, or adjudication activities.

But, finding these cut-n-pasted sections of the budget only gets us so far. I had 1200 different budget provisions, most of which were NOT cut-n-paste, so the ‘butterflies’ and other unusual provisions could still be hiding anywhere.

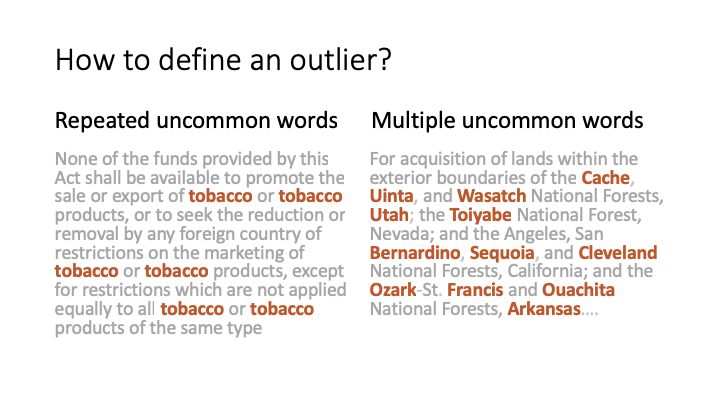

Doing some traditional cluster analysis also uncovered a bit of a problem with my project proposal: If most of the words in the budget classify as ‘rare words,’ what exactly was I going to look for again?

While I had a general idea that I wanted the ‘weird’ budget entries, I didn’t have an idea of what that might mean mathematically. The entry on the left has an unusual word that is repeated multiple times. The document on the right has multiple unusual words that each appear only once. Depending on the preprocessing and goals of the metrics chosen, either might be considered further from a ‘normal’ budget document.

Since my butterfly document had only one occurrence of the word ‘butterfly’ in it, I decided that even if a word is only mentioned once, it may be important. I kept all my unique words in my dictionary, but this makes the budget harder to organize automatically.

Word similarity

Since I had so few words that were exact matches, I experimented with tools that would cluster words that were not an exact match but had still had similarities.

Word2Vec and Glove are two methods for grouping words based on the their contexts. The idea is that a word has similar meaning as another word if it has the same words next to it or one word over. In other words, if the nearby words are the same, then two words are related even if the words themselves are not identical. There are pretrained word vector models available for download that have been trained on millions or billions of words.

Word similarity measures can be applied at the level of individual words or at the document level.

Clustering individual budget words

I clustered individual budget words based on their proximity in a pretrained word vector model, and found some clusters that made logical sense:

Energy policy ‘supply’, ‘energy’, ‘gas’, ‘oil’, ‘mining’, ‘fuel’, ‘coal’, ‘crude’, ‘petroleum’, ‘demand’, ‘electricity’

Latin America ‘mexico’, ‘colombia’, ‘guatemala’, ‘honduras’, ‘venezuela’, ‘nicaragua’

Public Health ‘prevention’, ‘avian’, ‘bird’, ‘contagious’, ‘disease’, ‘infectious’, ‘outbreak’, ‘aids’, ‘suffer’, ‘ebola’, ‘virus’, ‘vaccine’, ‘pathogen’, ‘immunization’, ‘malaria’, ‘polio’, ‘tuberculosis’, ‘severe’, ‘illness’, ‘epidemic’, ‘bacterial’, ‘infection’, ‘vaccination’

And some that were less helpful:

??? ‘redesignate’, ‘disaggregate’, ‘adulterate’, ‘effectuate’, ‘prorate’, ‘subleasing’, ‘urbanize’, ‘repurpose’

??? ‘necessary’, ‘need’, ‘good’, ‘able’, ‘time’, ‘way’, ‘know’, ‘particular’, ‘kind’, ‘help’, ‘example’, ‘fact’

If my customer were particularly interested in public health, this would give me a great starting point to search for related budget provisions. But, I did not get a complete list of topics. For example, there’s no clear border patrol cluster, despite the clear poitical interest in border issues reflected in the budget. The word ‘butterfly’ did not appear in what seemed to be the environment-related cluster, either.

Regularization (broadly speaking, this is a way of relaxing a model to reduce overfitting and bias) increased the number of words that would cluster, but it also increased the number of clusters that were seemingly meaningless and even broke down some of the useful clusters into less helpful subsets. Tuning regularization is difficult in unsupervised machine learning: grouping English words for human meaning is not the same as the mathematical closeness in a word vector model.

Using word vectors at the document level

One big trade-off to using a word2vec model that words are now represented as dense vectors, while the naive matching-word representation is a sparse vector (in other words, a list of numbers that is mostly zeros). It’s quick and easy to addition or multiplication with zero versus with a long list of non-zero numbers. This affects both the tools that can be used to compared documents as well as computation time.

Gensim provides a distance metric for comparing documents that takes word similarity into account. It is called the ‘Word Mover Distance.’ To calculate this metric, each word in one document is matched with one more more words in the other document, and the distance is weighted based on word similarity scores.

Because this metric is slow to compute, I only used the documents of length 10 to 100 words (after removing stop words). This represented 942 of my original 1248 documents.

It’s hard to compare results directly with the earlier attempt at clustering because the data set was shortened, however it did seem to be somewhat of an improvement. 112 documents grouped into clusters of similarly structured budget entries (that were not all cut-n-paste) that could be eliminated in our search for unusual entries. That still left 830 unclustered documents that would have to be analyszed further. With regularization, the butterfly provision was in a subset of 700 unclustered documents. But, again, without looking at the results manually, it is hard to tell what whether changing the regularization parameter was actually making things better versus worse, and 700 documents is still a lot for a researcher to have to sift through manually.

Results

While writing and debugging my code, I definitely found the sorts of things that I was looking for (buried amidst plenty tedious legalese). The authorship committees were clearly concerned with various border and immigration issues, but there were also unique provisions benefitting, for example, the sugar beet industry in Oregon.

I still believe there are interesting results to be found by examining the ‘strings’ Congress attaches to the budget for an individual year or over time. But, so far it would take humans to tag and cateogorize the items, as I did not find a reliable way to organize the entries in the federal budget using unsupervised machine learning.